by Ethan Velez

I was still quite young when my mother told me about her dream where she found me having sex with another man. Since I was born I could identify the subtle, non-verbal, blink-and-you-miss-it displays of what my parents were thinking and feeling. When my mother told me about her dream, I saw her bewildered eyes, her lowered lips, her shoulders turned away from me. I concluded I needed to apologize to her, so I did.

I found myself apologizing for many things that way. My grandmother didn’t like my father, so after I was born with his face, I apologized to her. When my father made me in his image, I apologized to him. When I fell in love for the first time, I apologized to her. Christopher Isherwood once described this medium as a series of little deaths: the denial of yourself for the endorsement of others. When I read this in his book, I wrote in the margins: “repenting: the denial of yourself for the endorsement of Christ?”

I saw the face of God in my mother’s love. So like many before me, I abided by God, I strived to make Him proud. I never disobeyed my mother. I was always there to protect her. That’s why her dream scared the shit out of me: because she had revealed to me the person she didn’t love, maybe even resented, and for a moment, he looked like me. For a moment, I stopped being her son. For a moment, I fell from the grace of God.

I was too young to know that the face of God was in all beautiful things, in the mundanity, in the night. All the beauty and the bloodshed, too. I saw it in my first kiss, in orgasmic sex, in the validation of a good grade, in a spliff with my morning coffee. In these moments, I didn’t feel compelled to apologize. In these moments, I lived where I once died. When Christopher Isherwood stopped suffering little deaths, he went to Berlin. I went to San Francisco.

I flew out to celebrate my birthday with my high school best friend. The neighborhood he lived in was frighteningly reminiscent of old Washington Heights: colorful street vendors, people on beach chairs under the sun, music playing from a kitchen window nearby. It had a heartbeat, a subtle thump you could feel beneath the pavement.

I was taking this all in the morning after my birthday. I spent it alone, leaving my friends behind to look for the cruising park. I learned about them from Al Pacino in Cruising and I read tales in John Rechy’s City of Night. I knew that cruising was queer history, that it was a dance. I also knew it sounded terrifying, and that I needed to know more. I trusted my trip to San Francisco to include impulse and bold abandonment of my senses. I found it in this park: this primal museum display of men with other men.

In the beginning, I wanted to repent. This wasn’t my first sexual or even queer experience, and yet I was again overcome with this need to apologize. I suddenly remembered through my upbringing that sex was wrong and humiliating. I felt untoward. I avoided everyone’s eyes. Then in deep breaths, I could smell fresh dirt and just-trimmed grass. I was back in my body. My mother wasn’t here, I told myself, so neither was God. Neither was shame.

I learned rather quickly that cruising was about patience and gratitude. We exclusively communicated in this subtle, non-verbal, blink-and-you-miss-it language I knew so well. I felt alive when I nodded or shook my head, when a hand stroked my arm or touched my shoulder. Eye contact felt glorious, smiling more thrilling than sex. The first man to look at me was tall, handsome, and patiently waiting for me to look back at him. (I found this to be the most appealing trait about him, that he was kind.) I pretended I loved looking at shrubbery until I couldn’t. When I finally looked back, we shared a smile, as if to say “Isn’t this so funny?”

There were buildings to the north of the park that hovered over us like a jury of unblinking giants. I imagined what I looked like to them, standing over a kneeling man who worshiped me in ways I previously thought was reserved for God.

On the flight back to New York, it was five am eastern time, and I was thinking about it all. Was I willing to exist outside of shame? Had I done that in San Francisco? When I landed, I started noticing my face in the reflective surfaces at JFK. Had I changed? Did I want to?

My mother was happy to see me. She waited for me at pickup and her joy from having me back was infectious. “I don’t know when you got so grown up,” she said endearingly, and it was somehow the greatest compliment I’ve ever received.

The parts of myself that are still afraid of the fall from grace exist in the Virgin Mary portrait above my bed, in the Saint Michael emblem in my foyer. In their company is the cock ring I bought in San Francisco, a framed photo of Al Pacino in the Godfather, a Tom of Finland print on my wall. I don’t apologize for the contradiction, I don’t want to. It’s here, too, in this complexity: the face of God.

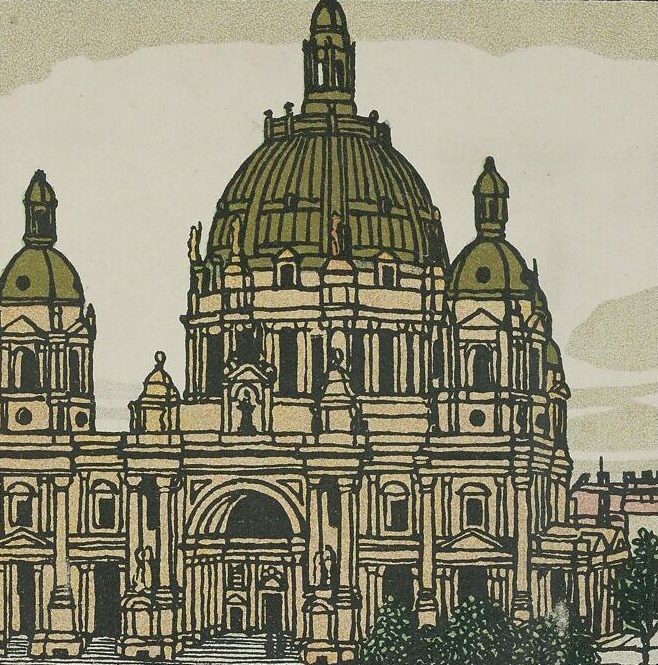

Photo Credit: Berlin: Cathedral (Der Dom), 1911 Gustav Kalhammer the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Ethan Velez is a writer and journalist based in New York City. He loves writing and believes it is something everyone should do. Some of his biggest inspirations include his mom and Nan Goldin.